FDA Approves At-Home Collection Device for Cervical Cancer Screening

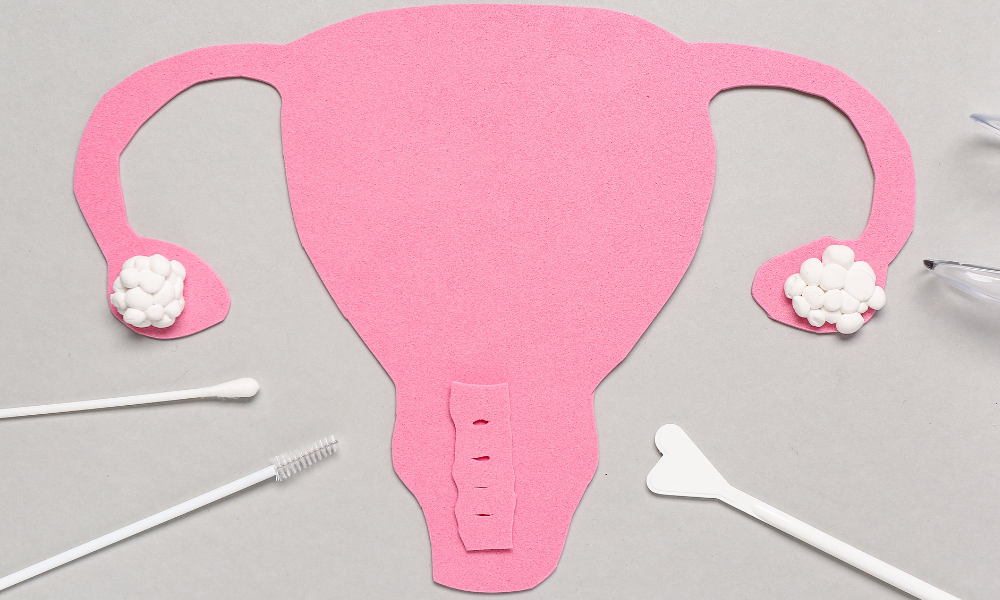

The FDA just approved the Teal Wand, a self-collection device for HPV testing that does not require a speculum exam or even a trip to the doctor’s office. People can collect their own sample at home and send it to a lab for analysis.