FDA Approves New Version of PrEP—Just Two Shots A Year

The FDA has approved lenacapavir as a form of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), offering a new option for HIV prevention requiring only two shots per year.

For the second year in a row, HPV vaccination rates among teens have not gone up according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The new report looked at health records for young people ages 13 to 17, as well as surveys of their families and health care providers. The authors analyzed data on all recommended vaccines for this age group to determine what percentage of young people are covered.

The HPV vaccine protects against nine types of HPV. This includes seven “high-risk” types associated with cervical cancer as well as cancer of the vagina, vulva, and anus. In the U.S., HPV infections are estimated to cause about 37,300 cases of cancer each year. HPV vaccination can prevent over 90% of these cancers from ever developing.

The HPV vaccine is part of recommended vaccinations given to adolescents at age 11-12, though it can be given as early as age 9. The vaccine is recommended for all adolescents regardless of biological sex or gender. Young people between ages 9 and 14 only need two doses of the HPV vaccine. Those who get the vaccine after age 15 must get three doses.

The new CDC report notes both the percentage of young people who got one dose of the vaccine and those who are “up to date,” meaning they had two or three doses depending on age.

In 2023, 76.8% of adolescents ages 13 to 17 years had received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine and 61.4% were fully up to date on the vaccine series. This was similar to the rates in 2022 when 76% of teen 13 to 17 had received at least one dose and 62.6% were up to date.

Before that, however, rates had increased every year since 2013. The report’s authors did additional analysis to help determine what’s behind this trend.

We know that the health care was interrupted during the pandemic. Many people missed routine medical care because offices were shut down.

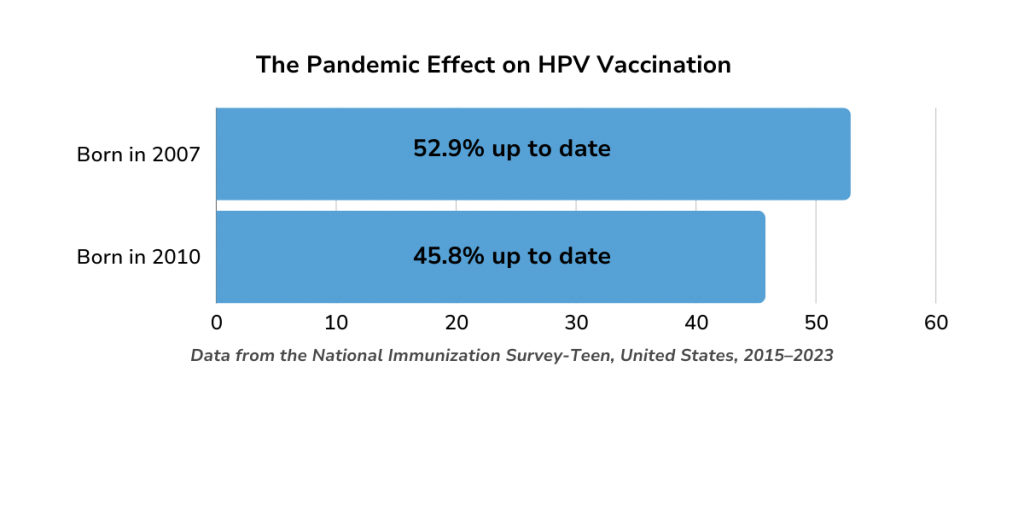

In an effort to understand the effect of the pandemic on vaccine coverage, researchers compared data from young people born in 2008, 2009, and 2010 to that of those born in 2007 who were of an age (17) that they should have received these vaccines before the pandemic.

At age 13, kids born in 2008 (who should have been vaccinated during the height of the pandemic) were less likely to have gotten their HPV shots (as well as other vaccines) than those kids born the year before. Even at 14 and 15 their vaccine coverage remained lower than kids born in 2007.

Routine vaccination rates seem to have recovered quickly post-pandemic. Young people born in 2009 and 2010, who would have been scheduled to get these shots after the pandemic, had similar coverage rates to those born in 2007. There was one notable difference, however: the percentage of adolescents born in 2010 who were up to date on their HPV shots as of last year was 7.1 percentage points lower than among those born in 2007.

The authors say this is a reminder that we have reach out to parents who may not have caught up with routine medical care since the pandemic about the importance of staying up to date on vaccines.

In 1994, the government established the Vaccines for Children (VFC) Program. The program provides free vaccines to children who are eligible for Medicaid, uninsured, or under insured, as well as to American Indian and Alaska Native children. Approximately 40% of teens in the U.S. are eligible for the VFC program.

Young people eligible for the program who were born between 2008 and 2010 had similar vaccine coverage as VCF-eligible adolescents born in 2007. There was one major difference, however; the percentage of VFC-eligible adolescents who were up to date with HPV vaccination was 10.3 percentage points lower among adolescents born in 2010 than those born in 2007. In past generations of young people—such as those born between 2002 and 2005—VCF-eligible adolescents were more likely to be up to date on their HPV shots than their peers.

The authors of the report said the decline among VFC-eligible adolescents might mean that the program has become less accessible and believe their findings “underscore the importance of ongoing efforts to ensure equitable access to vaccination services for all children and adolescents.”

We know that HPV vaccines are starting to have an impact because infection with the types of HPV covered by the vaccines have dropped by 86 percent among teen girls. The full potential of these vaccines to prevent cancer, however, will only be reached if more young people received them.

The FDA has approved lenacapavir as a form of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), offering a new option for HIV prevention requiring only two shots per year.

On a recent episode of Love Island, a cast member sugested that we could blame our current STI epidemic on men who had sex with animals. She pointed to koalas with chlamydia as an example. There’s some truth here, but also a lot of misinformation.

A new report from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) shows that we’re missing opportunities to prevent congenital syphilis and save lives.

Currently, condoms are the only widely available, proven method for reducing transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) during sex. Condoms work.

Anal sex may have once been thought of more taboo than other sexual behaviors, but today we know it’s a perfectly normal way to find sexual pleasure.

It’s time to celebrate the start of summer! June is filled with national observances to help you start the summer off right. We’re here to help make June the start of a #safesexysummer.

There’s potential good news in gonorrhea prevention as a series of studies suggests that certain meningococcal B (MenB) vaccines can reduce the risk of gonorrhea.

There is new guidance on pain management for IUD insertion and acknowledgement that providers often underestimate the pain patients feel during their procedures.

ASHA believes that all people have the right to the information and services that will help them to have optimum sexual health. We envision a time when stigma is no longer associated with sexual health and our nation is united in its belief that sexuality is a normal, healthy, and positive aspect of human life.

ABOUT

GET INVOLVED

ASHA WEBSITES

GET HELP

© 2025 American Sexual Health Association