All About Condoms

Currently, condoms are the only widely available, proven method for reducing transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) during sex. Condoms work.

The name says it all. Long-acting reversible contraception, or LARC, is reversible birth control that provides long-lasting (think years) pregnancy prevention.

While not currently the leading choice among women, LARC use has been on the rise in recent years. In women aged 15-44, the rising popularity of LARC can likely be attributed to its high rate of effectiveness (more than 99 percent) and ease of use.

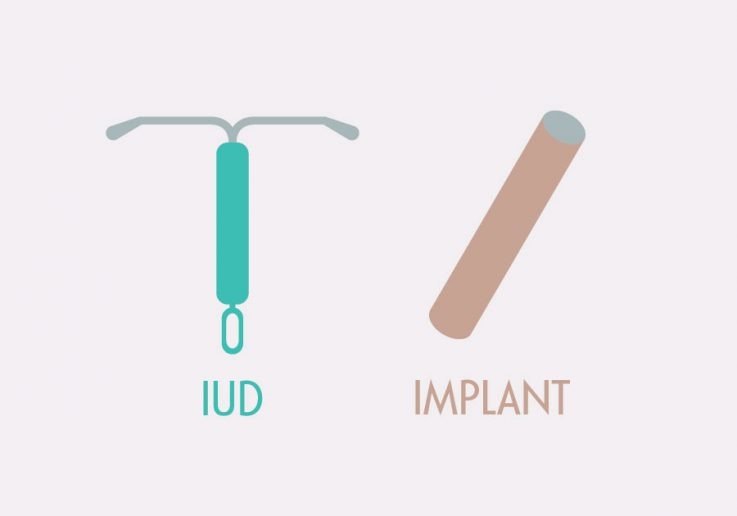

LARC methods—intrauterine devices (IUDs) and implants—are highly reliable. Research has shown LARC methods to be 20 times more effective than birth control pills, the patch, or the vaginal ring.

One important reason why is the LARC removes the “user error” factor that can make other methods less effective. No need to remember to take a pill daily, or have a diaphragm on hand ready to go. Once a LARC is in place, it does its job for years with no input from the user at all, acting as a “set it and forget it” method.

But there’s one thing that shouldn’t be forgotten—protecting against sexually transmitted infections (STIs). While LARC is a highly effective way to prevent pregnancy, LARC methods don’t provide any protection against STIs. For this reason, many people choose to use (and health professionals recommend) condoms in addition to a LARC method. Dual use of condoms and LARC offers dual prevention.

There are two LARC methods: the intrauterine device (IUD) and the birth control implant. The intrauterine device (IUD) was once a popular choice in the U.S., but following problems linked to the poorly designed Dalkon Shield model in the 1970s, usage dropped due to concerns about safety. A new generation of IUDs was introduced in the early 2000s, and today’s models have none of the earlier safety concerns. But some misconceptions still persist.

The birth control implant has been available in the United States since the 1990s. The earliest model, Norplant, included multiple rods implanted under the skin on the inner arm. It offered pregnancy prevention for up to five years. While it was easy to insert, some people experienced problems with the removal procedure, and the manufacturer had issues finding the ingredients it needed to make the product.

Norplant was taken off the market in 2002, and a new generation of implants, now called Nexplanon, was introduced a few years later. This device consists of only one small rod, and both insertion and removal are easy.

The history of contraceptive implants is also complicated by coercive practices that emerged almost immediately after Norplant became available. Several states introduced legislation mandating its use in specific groups of women, including those receiving public assistance. In addition, some women facing court charges, such as child and abuse and neglect, were offered the option of accepting implants in exchange for a reduced sentence. Like so many coercive practices, Black and brown women were disproportionately impacted.

Understanding and acknowledging this history of coercive use of LARC and safety concerns is important, to avoid problems of the past. But so too is understanding the potential value of current LARC methods.

IUD: An IUD is a small T-shaped device that is inserted into the uterus by a health care provider. It works by preventing sperm from reaching and fertilizing an egg. Some IUDs contain hormones like these in birth control pills that can also prevent ovulation (so there is no egg to be fertilized) and thicken cervical mucus (to make it harder for the sperm to get into the uterus).

All IUDs have a string that hangs through the cervix into the vagina to make removal easy. Anyone who has an IUD can check that it’s still in place by putting a finger into their vagina and feeling for the string.

There are two types of IUDs:

IUD Insertion

IUDs have to be inserted by a health care provider. The provider uses a speculum to hold open the vagina and then uses a special tool to insert the IUD through the cervix and into the uterus. The process can be done at any point during the menstrual cycle and only takes 5 to 10 minutes.

Some people find the procedure mildly uncomfortable, like typical menstrual cramps, while other people say it is quite painful. The CDC recommends that providers offer various pain relief options to people getting an IUD inserted. (See LARC Questions and Concerns for more information about the types of pain relief available.)

IUD Removal

While IUDs can remain in place for years, they can also easily be removed if a person decides they would like to become pregnant or does not like the method. The removal process is easier and less painful than insertion.

Complications

Most people have no issues with the IUD. Some users, especially those who have a hormonal IUD, say they like this method because they don’t get their period. Other users report spotting between periods, and some people with Paragard report a heavier flow.

There are some rare but serious problems that can occur with IUD use. IUDs can slip out of place, be expelled from the uterus, or pierce the uterine wall. This usually happens within the first few months after insertion. Learn more about IUDs and hear stories from real women who use this method at Bedsider.

Implant: The birth control implant is a single small, thin rod that is inserted under the skin of a women’s upper arm by a healthcare provider. The rod releases the hormone progestin into the body, which both helps prevent ovulation and thickens cervical mucus, helping prevent sperm from reaching an egg. The implant prevents pregnancy for up to 3 years.

As with the IUD, the implant can be removed at any time if a woman decides to get pregnant. The most common side effect is irregular bleeding—including spotting between periods and heavier periods. This typically improves over time. Learn more about implants and hear stories of women using this method at Bedsider.

So with all the potential benefits, why is LARC not a more popular choice? One reason is the large upfront cost. Both methods must be inserted by a physician and costs cannot be spread out over time as with other methods. The good news is that under the Affordable Care Act, all insurance plans in the health insurance marketplace must cover all FDA-approved contraceptive methods prescribed by a doctor, including LARC.

There is also a lot of outdated information about LARC. Older versions of IUDs, for example, were not considered safe for young patients or patients who had not yet had children. This is no longer true, but some people and even some health care providers continue to believe it. Such concerns are misplaced—the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that LARC methods be offered as first-line birth control methods and encouraged as options for most patients, including adolescents and patients who have never had children.

LARC methods offer a safe, long-lasting choice for preventing pregnancy—one that requires no real thought or effort over years. It’s an option that most patients should consider a viable choice.

Currently, condoms are the only widely available, proven method for reducing transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) during sex. Condoms work.

There’s potential good news in gonorrhea prevention as a series of studies suggests that certain meningococcal B (MenB) vaccines can reduce the risk of gonorrhea.

There is new guidance on pain management for IUD insertion and acknowledgement that providers often underestimate the pain patients feel during their procedures.

Non-hormonal contraceptive methods fall into a few categories. These include barrier methods and surgical options.

There’s new research to suggest that the birth control pill can protect female athletes from ACL tears which is one of the most common knee injuries. While this may sound far-fetched, the science behind it is very interesting.

A new study of more than 200,000 women found that women who had ever taken the pill had a 26% lower risk of ovarian cancer.

Many methods of birth control that are available today rely on hormones like those that our bodies make naturally. Hormonal methods come in many different forms—from pills to patches to shots—but all of them essentially work the same way.

Anyone who is having penis-in-vagina sex runs the risk of getting pregnant every time they have sex. Even if it’s your first time. Even if you have your period. Even if it’s a full moon and Mercury is in retrograde.

ASHA believes that all people have the right to the information and services that will help them to have optimum sexual health. We envision a time when stigma is no longer associated with sexual health and our nation is united in its belief that sexuality is a normal, healthy, and positive aspect of human life.

ABOUT

GET INVOLVED

ASHA WEBSITES

GET HELP

© 2025 American Sexual Health Association